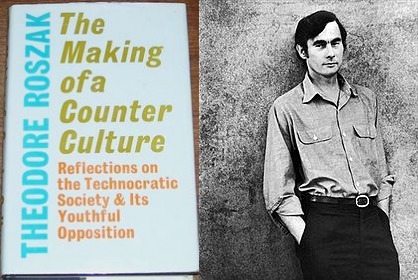

The making and breaking of the counter culture

Last week I came across a small book called The Making of a Counter Culture, written in 1969 by an American historian called Theodore Roszak. I loved it. Roszak was the first to coin the phrase ‘the counterculture’. His book gives one a whiff of the heady atmosphere of San Francisco (and Paris, and London) in 1968-9, when imagination was liberated and all things seemed possible.

Roszak sensed something in the air. He sensed there was a cultural revolution happening among university students, and it was in many ways a religious revolt, a wave of Gnostic mysticism, a throwing-off of the iron cage of technocracy in favour of intimacy and ecstasy. It was a religious revival, but not as the evangelicals imagined it. Aldous Huxley was closer to the mark. Roszak writes:

in the 1950s, as Huxley detected the rising spirit of a new generation, his utopian image brightened to the forecast he offers us in Island, where a non-violent culture elaborated out of Buddhism and psychedelic drugs prevails. It was as if he had suddenly seen the possibility emerge: what lay beyond the Christian era and the ‘wasteland’ that was its immediate successor might be a new, eclectic religious revival. Which is precisely what confronts us now as one of the massive facts of the counter culture. The dissenting young have indeed got religion. Not the brand of religion Billy Graham or William Buckley would like to see the young crusading for – but religion nonetheless.

Just as Huxley predicted, the new religious landscape which appeared in the 1960s was eclectic, with young people trying out many different practices, from Zazen to the I-Ching, from indigenous psychedelic rituals to the Tibetan Book of the Dead. Did they understand it all? Not entirely. Roszak wrote:

At the level of our youth, we begin to resemble nothing so much as the cultic hothouse of the Hellenistic period, where every manner of mystery and fakery, ritual and rite, intermingled with marvellous indiscrimination...No, the young do not by and large understand what these traditions are all about. One does not unearth the wisdom of the ages by shuffling about a few exotic catch phrases – nor does one learn anything about anybody’s lore or religion by donning a few talismans and dosing on LSD. The most that comes of such superficial muddling is something like Timothy Leary’s brand of easy-do syncretism: ‘somehow’ all is one – but never mind precisely how. Fifty years ago, when Swami Vivekananda first brought the teachings of Ramakrishna to America, he persuaded a clique of high-society dilettantes to believe as much. The results were often as ludicrous as they were ephemeral. Yet things are just beginning in our youth culture.

Huxley (like Blake before him) complained that rationalist western culture had marginalized mystical ecstasy in favour of instrumental technocracy. We have become estranged from the non-rational aspects of our consciousness. Roszak blames academia for this spiritual estrangement:

As the spell of scientific or quasi-scientific thought has spread in our culture from the physical to the so-called behavioural sciences, and finally to scholarship in the arts and letters, ,the marked tendency has been to consign whatever is not fully and articulately available in the waking consciousness for empirical or mathematical manipulation, to a purely negative catch-all category (in effect, the cultural garbage can) called the ‘unconscious’…or the ‘irrational’…or the ‘mystical’…or the ‘purely subjective’. To behave on the basis of such blurred states of consciousness is at best to be some species of amusing eccentric, at worst to be plain mad.

Hippy students rejected this and demanded an education for their whole selves. He wrote:

I think we can anticipate that in the coming generation, large numbers of students will begin to reject this reductive humanism, demanding a far deeper examination of that dark side of the human personality which has for so long been written off by our dominant culture as ‘mystical’.

It is quite impossible any longer to ignore the fact that our conception of intellect has been narrowed disastrously by the prevailing assumption, especially in the academies, that the life of the spirit is (1) a lunatic fringe best left to artists and marginal visionaries; (2) an historical boneyard for antiquarian scholarship; (3) a highly specialized adjunct of professional anthropology; (4) an antiquated vocabulary still used by the clergy, but intelligently soft-pedalled by its more enlightened members. Along none of these approaches can the living power of myth, ritual, and rite be expected to penetrate the intellectual establishment and have any existential (as opposed to merely academic) significance. If conventional scholarship does touch these areas of human experience, it is ordinarily with the intention of compiling knowledge, not with the hope of salvaging value.

He saw the counter culture as a marriage between New Left politics (the anti-war movement, the free speech movement, the principles laid out in the Port Huron statement of the Students for Democratic Society) and the bohemianism and spiritual eclecticism of the commune. He called it ‘the politics of consciousness’:

We grasp the underlying unity of the counter culture if we see beat-hip bohemianism as an effort to work out the personality structure and total life style that follow from New Left social criticism. At their best, the young bohemians are the would-be utopian pioneers of the world that lies beyond intellectual rejection of the Great Society.

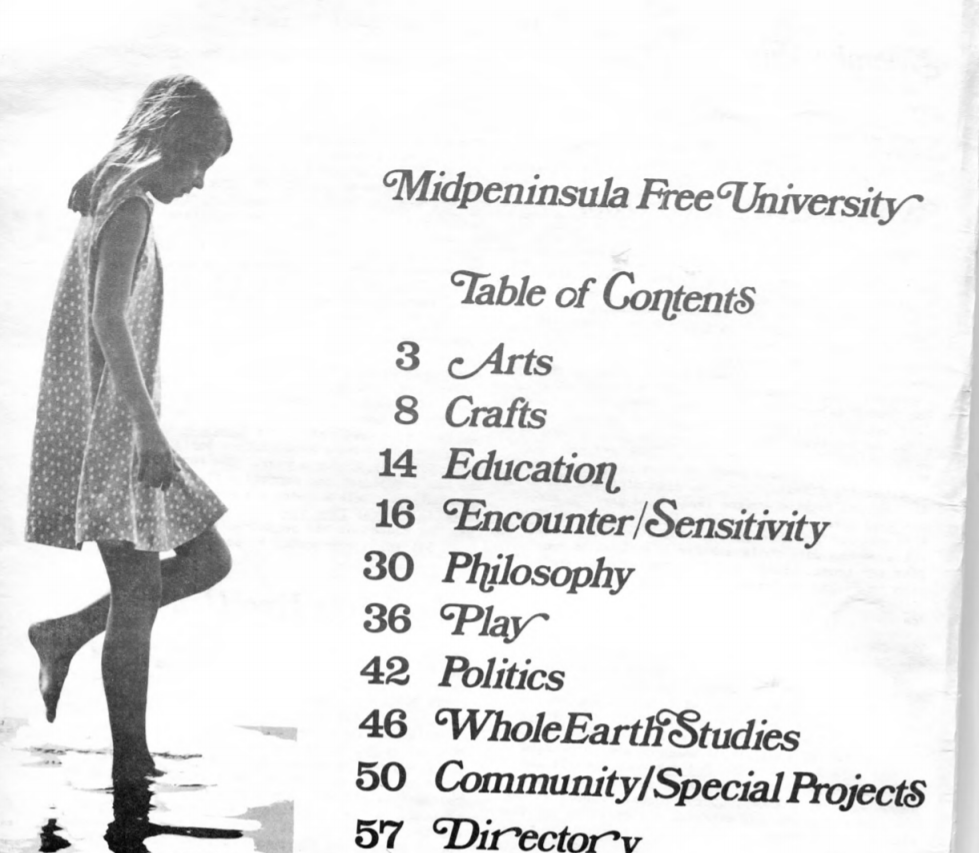

He suggests one can see students’ appetite for spiritual experimentation and mystical experience in the free university movement. In the second half of the 1960s, students and teachers across the US started up alternative campuses offering free classes. At one of the most famous, the Mid Pensinsula Free University near Palo Alto, visiting teachers included Joan Baez, Stewart Brand, Herbert Marcuse and Richard Alpert / Ram Dass. It offered classes in everything from LSD to psychodrama, from Taoism to non-violent resistance. It was a manifestation of Aldous Huxley and Alan Watts’ dream of an integral education that included the mystical and connected it to the political and ecological. 'The natural state of man is ecstatic wonder', declares its syallabus. 'Why settle for anything less?' Why indeed! I've had to censor the images from their syllabus...

Their syllabuses look so wonderful from the perspective of 21st century technocratic academia, when even a course on happiness seems a bit out there. But we’ve seen the faint stirrings of a similar mystical wave in recent years. The Occupy Wall Street / Occupy London protests included free universities, and those movements have continued at Occupy KCL, Occupy LSE and other campuses, although these don’t strike me as very spiritual movements. We’ve also seen the growth of adult education organisations offering psycho-spiritual education (for a price). In London, you have places like The Psychedelic Society, Rebel Wisdom, The Weekend University, the London Philosophy Club, the House of Togetherness, Mantra and the Experimental Thought Company. Still pretty tame compared to MFU.And yet these spiritual stirrings still feel quite marginal to mainstream western culture. The capitalist technocracy was not overthrown, like Roszak predicted, nor was even university education much affected. Why didn’t the counter culture establish itself as the mainstream culture? Why did it fail?

One reason is that 1968 was the peak of a mystical wave, and those waves always pass. The flame of charisma requires the coal of institutions, with proper business plans, otherwise the flame soon burns out. The free universities didn’t have proper business plans (they were free). People need jobs.

A second issue, one identified very well by Roszak, was that the counter culture fetishized psychedelics as the only route to enlightenment. Huxley and Alan Watts said they were a route, one not to be taken without proper preparation. But Timothy Leary (who Huxley called an ass) tried to create a religion of LSD, insisting everyone should take it, even teenagers – his own teenage daughter took acid, went mad and later committed suicide. Most American teenagers simply didn’t have the cultural or emotional equipment to make sense of psychedelics. Roszak writes:

There is nothing whatever in common between a man of Huxley’s experience and intellectual discipline sampling mescaline, and a fifteen-year-old tripper whiffing airplane glue until his brain turns to oatmeal. In the one case, we have a gifted mind moving sophisticatedly towards cultural synthesis; in the other, we have a giddy child out to ‘blow his mind’ and bemused to see all the pretty balloons go up. But when all the balloons have gone up and gone pop, what is there left behind but the yearning to see more pretty balloons?

At the level of disaffiliated adolescence, the prospect held forth by psychedelic experience – that of consciousness expansion – is bound to prove abortive. The psychedelics, dropped into amorphous and alienated personalities, have precisely the reverse effect: they diminish consciousness by way of fixation…What is obvious….is that the psychedelics are a heavyweight obsession which too many of the young cannot get over or get around.

He quotes a ridiculous article in the Village Voice, which asks: ‘CAN the World Do Without LSD? Can a person be human without LSD?... The answer, as far as the writer of this article can see, is a highly qualified, cautiously rendered, but emphatic, definitely NOT. BUT the psychedelic experience is not exclusively tied to LSD. There are at least give other effective psychedelic drugs.’

Another reason, perhaps, that the counter culture fails is it was badly marketed as a revolt against all previous traditions and against one’s elders. As Michael Pollan points out, mystical initiations are usually embedded in a culture, with elders initiating the youth through ritual. In the psychedelic counter culture, the youth initiated themselves through a ritual their parents couldn't understand. Usually, ritual binds society together, in the sixties, it tore it apart.

The counter culture was also, in Roszak’s telling, a revolt against science and reason. He writes that, to bring back ecstasy,

'nothing less is required than the subversion of the scientific worldview, with its entrenched commitment to an egocentric and cerebral mode of consciousness. In its place, there must be a new culture in which the non-intellective capacities of the personality take fire'.

That’s a mistake. As Huxley said many times, you need the best of both worlds – the rational and the non-rational, the scientific and the aesthetic, the mystical and the practical. Roszak’s revolution sounds like mystical fascism, particularly when he calls for a collective assault on the ego:

[the counter culture] attacks men at the very core of their security by denying the validity of everything they mean when they utter the most precious word in their vocabulary: the word ‘I’. And yet this is what the counter culture undertakes when, by way of its mystical tendencies or the drug experience, it assaults the reality of the ego as an isolable, purely cerebral unit of identity.

I am all for building a culture dedicated to ego-transcendence. But the process both for the individual and for society needs to be gentle, slow, and voluntary, not some sort of Manson-esque revolt where you put LSD into the water.

When the 1968 mystical revolt failed, when it failed to overthrow capitalism, failed to stop the election of Richard Nixon, failed to stop the Vietnam War, then the counter culture turned nasty – Timothy Leary and many others embraced violent revolution and spiritual enlightenment through bombs. The MFU went Maoist. Most of the baby-boomer generation simply grew up, got a job, and conducted their spiritual and sexual experimentation in their private lives, at the weekend. Roszak writes sadly:

It would be one of the bleakest errors we could commit to believe that the occasional private excursions into some surviving remnant of the magical vision of life – something in the nature of a psychic holiday from the dominant mode of consciousness – can be sufficient to achieve a kind of suave cultural synthesis combining the best of both worlds. Such dilettantism would be a typically sleazy technocratic solution to the problem posed by our unfulfilled psychic needs, but it would be a deception from start to finish. We have either known the magical powers of the personality or we have not. And if we have felt them move within us, then we shall have no choice in the matter but to liberate them and live by the reality they illuminate.

Well, that’s exactly what happened. People wearily accepted five days of technocratic capitalism, and then a bit of cocaine at the disco on Saturday night, and maybe a car-key party for afters.

Maybe now the baby-boomers have grown old, the counter culture is finally becoming mainstream. Maybe ego-transcendence is becoming more accepted, even in academia, even in scientific research. It’s a bit late now, with the Earth hotting up in real time. But perhaps something will survive, and a better, more mystical-ecological culture will emerge out of the ashes.

For a great website all about the Mid Peninsula Free University, go here.