The Myth of Religious Violence

We all know the story. Europe in the 17th century was torn apart by the Wars of Religion. Then, after several decades of extreme violence, people decided to put religious differences to one side, and to come together in the rational, secular, liberal, tolerant state. We then exported this model of rational civilisation to the rest of the world, which is slowly accepting it, despite being backward, irrational and prone to religious violence (that means you, Muslims).

This is the foundational myth of the modern secular state. And like all myths, it is not entirely true. Its falsehood - or limited truth - can blind us to our own irrational violence.

Ecstasy plays a key role in this myth. Ecstatic experiences were central to the Christian conception of human nature and human society. Ecstasy was the ladder which connected humans to the divine. But in the 17th and 18th century process of secularization, ecstasy was rebranded as ‘enthusiasm’, and deemed a mental illness and a threat to public order. Enthusiasm was the ‘anti-self of the Enlightenment’, the enemy of reason. Ecstasy has to be locked up or banished if the rational liberal secular order can exist.

The pathologisation of ecstasy began in the 16th-century Reformation. Martin Luther mocked the monastic practice of trying to reach ecstasy through contemplation - monks and nuns were lazy fools getting rich off the gullible masses. You can't get to heaven through your own contemplative efforts, only grace can save you. It is dangerous to rely on personal revelation or visionary experience, you should only rely on Scripture. Luther lambasted Anabaptist peasants for using personal revelation as a justification for violent revolution, calling them ‘enthusiasts’.

His critique of the Church was used by kings in their attempts to seize power and money for their fledgling states. Henry VIII, for example, embraced the Reformist cause to increase his own power in England. His advisors, Thomas Cranmer and Thomas Cromwell, used a Lutheran critique of monasticism to close down almost all the monasteries and nunneries in England and seize their assets. This is what secularisation originally meant - the transfer of assets and power from the church to the state.

Cranmer and Cromwell waged a war on ecstasy. When a Catholic nun called Elizabeth Barton prophesized against Henry and Anne Boleyn, she was hanged for treason. Thomas Cromwell declared: ‘If credence should be given to every such lewd person as would affirm himself to have revelations from God, what readier way were there to subvert all common wealth and good order in the world?’ Cranmer took the traditional invocation of the Holy Spirit out of the Book of Common Prayer. The Holy Spirit was deemed a threat to public order. Religion was reduced to a series of propositions, set by the state, which people must publicly affirm…or else.

In the 17th century, both Catholic and Protestant thinkers warned against ‘enthusiasm’ or any claim to personal revelation. It was a threat to reason and public order. One sees the political usefulness of this critique particularly in Thomas Hobbes’ remarkable polemic, Leviathan, published in 1651. Like a 17th-century Richard Dawkins, Hobbes rails against people who let their imagination carry them away, so that they start imagining fairy tales of God or angels or fairies speaking to them and telling them what to do. Such enthusiasts may then persuade the ignorant mob, who then disturb the public order and threaten the state.

This polemic against religious ecstasy is grounded in Hobbes’ materialism. We are material automatons. There is no such thing as a ghost in the machine or a Holy Spirit ‘out there’, no way any spirit could enter our bodies. Imagination is merely ‘decaying sense’, not some sort of ladder to the divine as medieval contemplatives believed. Medieval scholastics thought human nature was double - matter and soul. But this is nonsense. We are just matter.

Hobbes’ materialism is tied to his politics. In medieval Christendom, humans’ double nature (body and soul) was reflected in the double authority of the Church and the State, the kingdom of Heaven and the kingdom of Earth. But Hobbes insists we mustn’t set up a ‘ghostly authority against the civil’. This is to set up a ‘kingdom of fairies’. There can be only one power, one authority, one kingdom - the state. The state is the true kingdom of heaven, and we owe it total allegiance. As for religion, that can be reduced to the basic proposition that Jesus is Christ. Who doesn't accept that?

Hobbes is unusually outspoken in his denunciation of religious enthusiasm, but one finds a similar idea in Enlightenment thinkers like Locke, Hume and Shaftesbury. Religious enthusiasm is a threat to public order. Religion should be confined to the private sphere, while the public sphere remains secular, rational and polite. Ecstasy is not all bad, as long as it stays a private individual experience. This is what the Romantic Sublime is essentially - a private, individual experience. But enthusiasm is very dangerous when it’s collective, and when it spills over into the public sphere. We don’t want to go back to the 17th century, to those terrible Wars of Religion. We owe our primary allegiance to the secular, rational state.

This story is still very active today. It defines how we think of Islamic terrorism. Some reference to the Wars of Religion often appears in defences of western secularism and attacks on Islamic irrationalism. The story goes something like this: ‘We went through a period of religious violence in the 17th century until we invented the rational secular state, and everything calmed down and got better. Religion leads to violence, it causes more wars than anything else. If only you Muslims could evolve out of your religious irrationalism and embrace western rationalism. We will defend secularism from your irrational attacks, and support secular regimes in the Middle East. We will bomb you into rationalism.’

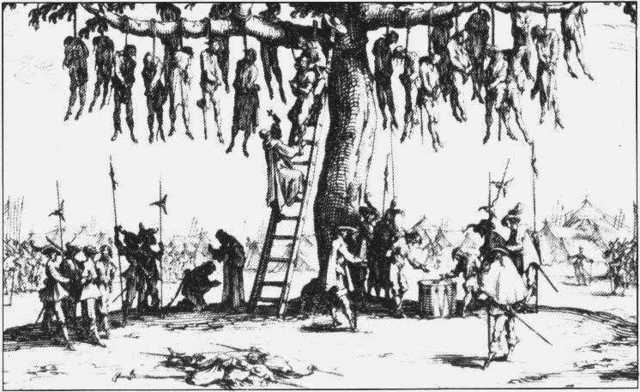

There are several problems with this ‘myth of religious violence’, as the historian William T. Cavanaugh calls it. Firstly, as Cavanaugh explores, it’s not an accurate account of the Thirty Years War, which was only dubbed the ‘Wars of Religion’ in the Enlightenment. Those wars often pitted Catholics against Catholics and Protestant against Protestants, in an ever-shifting series of battles which have more to do with the breakdown of the Hapsburg empire and the emergence of autonomous states than religious enthusiasm. As Peter Wilson concluded in his recent history, the emergence of the secular state wasn’t the antidote to the Thirty Years War - it was the cause of it.

Secondly, ecstasy and enthusiasm didn’t go away in the rational secular state. It took new forms, such as the capitalist ecstasy of the South Sea Bubble. Its most obvious new form was nationalism - the ecstatic worship of the state and state power. You can see this ‘migration of the Holy’ to the secular state in the French Revolution, in the cult of Napoleon, in the totalitarian worship of Hitler and Stalin, and - in a less extreme but no less powerful way - in American civil religion and the cult of the Star-Spangled Banner. Secularism didn’t really privatise religion, it created a new religion of the state.

Nationalist enthusiasm can be just as brutal, irrational and aggressive as medieval ecstatic movements. Nationalism caused far more wars and loss of life in the 19th and 20th centuries than monotheism. We think of secularism as tolerant and peaceful, but it often means state absolutism of a very brutal kind. That's certainly what it meant in the Middle East, with the Hobbesian regimes of Ataturk, Mubarak, Saddam Hussein, the Shah of Iran, or Hafez al-Assad. Today, Western societies are in danger of reacting to Islamic terrorism by embracing a particularly nasty nationalism, as peddled by Putin, Trump and Le Pen. Who, faced with such Leviathans, would not yearn for God?

Secularism is often tied to an aggressive materialism which many people - including me - find suffocating, soulless and unreal. If you want to win the battle of ideas with Islamic extremism, you cannot simply preach secularism, nationalism and materialism. That will not do the job. People will always yearn for a transcendence beyond the human, particularly the young, the poor and the oppressed. We need to create and protect spaces for transcendence in secular liberal cultures, so that young people don’t feel they have to go to violent extremes to find it.