The Master: self-help, and the Puritan longing to escape the past

Paul Thomas Anderson’s latest film, The Master, tells the story of drifter Joaquin Phoenix’s relationship with the head of a New Age sect, which looks suspiciously like Scientology. The group, called The Cause, aims (like Scientology) to clear its members of the karmic traces of their past lives, and return them to their inherent perfection. They do this by hypnotising their members to retrace their past incarnations, or by subjecting them to a battery of psychometric tests with questions like ‘why do you loiter at bus stops?’

Like Scientology, the Cause records all these confessions through microphones, to create a huge database of confessions. I find the technology of spirituality fascinating - all the gadgetry that humans have invented over the millennia to help us escape the material prison, from shamanic regalia, to the confession box and rosary, to the orgone box and the dianetics machine of modern 'scientific' religion. We want to escape materiality and come closer to God, yet when we look behind the veil of religions and cults, we often see little more than cheap stunts, pseudo-science and tawdry showmanship.

The head of the Cause, played by Philip Seymour Hoffman, is part-Svengali, part-PT Barnum. One is never sure how much he believes his own hype. For almost all of the film, he is a flouncy performer, playing up to his adoring devotees. Only once do you see him alone, off-stage, looking out through the slats of a blind at the empty stage and the crowd awaiting him. Briefly, you see the lonely soul trapped within the public persona, the diminutive figure behind the Wizard of Oz, the child longing to stop the pretense. He declares, when he first meets Phoenix, "I am a writer, a doctor, a nuclear physicist, a theoretical philosopher...but above all I am a man" - you wonder if he wishes he was just the latter.

Phoenix, meanwhile, is unbearably compelling to watch. His very skin and veins seem to pulsate with trapped animal energy. He is Caliban to Hoffman’s Prospero, hoping for escape from his tormenting spirits and demonic compulsions, while Hoffman’s faux-guru is drawn to him precisely for his wildness, his spontaneity, his authenticity and the promise he carries of escape from responsibility.

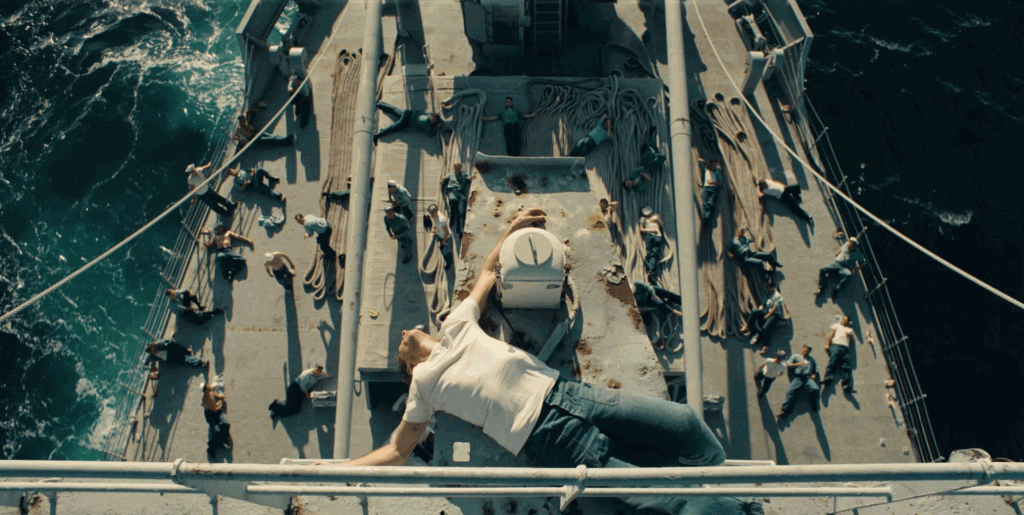

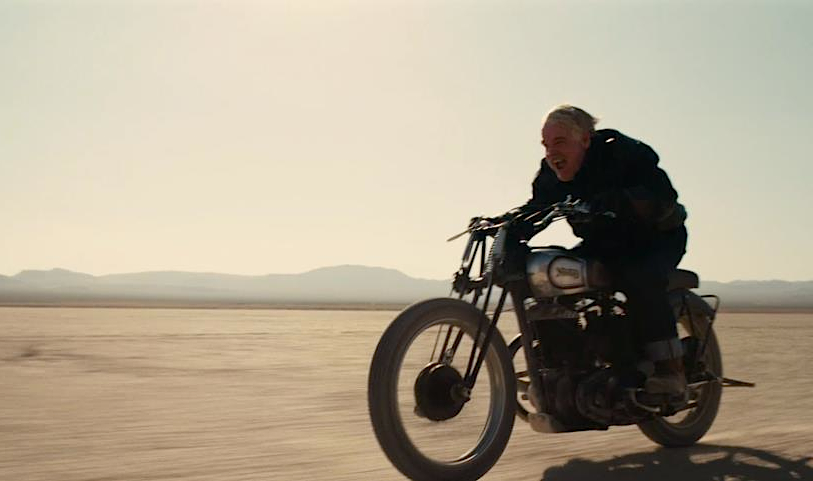

The film, like the Great Gatsby, is a powerful meditation on how the Puritan desire to escape the sinful past takes some very weird forms in modern American culture. You realise both the main protagonists are trapped in their past, in their roles, both dreaming of escape, both destined to fail. The past stretches out behind us, like the wake of a ship (in one of the film's recurring images). We can try to outpace it, like Phoenix riding a motorbike at breakneck-speed across the desert and into the horizon. But when we arrive, our past is already there, with all its claims upon us.

It reminds me of the old Looney Tunes cartoon, where an escaped convict is being hunted by Droopy, the lethargic basset-hound. No matter how far and fast the convict runs away, somehow Droopy is always there, waiting for him.

This is cinema that proves a close-up of an actor utterly inhabiting their character can be more breath-taking than any 3D spectacular. Anderson continues to explore the rocky terrain of modern loneliness and our yearning for community, forgiveness and transcendence. In contemporary American cinema, he is the Master.

*****

In other news:

The new report of the Schizophrenia Commission decided that the treatment of people with schizophrenia in NHS care is often "shamefully bad", and makes patients worse not better. Bullying orderlies (usually poorly-educated African immigrants) hand out the drugs and then leave the patients to bounce off the walls...That's certainly been the case in my experience (one of my close friends has had schizophrenia for two decades, and has spent the last three years in awful NHS homes). We can and must do better.

In China, the new government has to cope with a more active citizenry who want better healthcare and welfare for workers.

In Taiwan, the prevalence of common mental illnesses has more than doubled, from 11.5% to 23%, in the last decade. It's not clear (to me at least) if that's the cost of faster economic growth or improved awareness of mental health issues.

In Australia, the health and well-being sector of the economy is booming. It's now the biggest employer as a sector, overtaking mining. Good news for women, as they take 80% of the jobs in the sector.

The Institute of Development Studies has a new report on 'resilience', a hot buzz-word in, both psychology and development policy. IDS warns the focus on resilience should not be used as an excuse to switch focus from poverty alleviation - people can be very resilient and still very un-well.

There are suddenly a lot of articles about MOOCs (massive open online courses) and how they're about to transform higher education. The New York Times declared it the 'year of the MOOC', economist Alex Tabarok noted that his TED talk has achieved three times as many 'teaching hours' than all the rest of his teaching put together; while Clay Shirky thinks MOOCs are about to do to higher education what Napster and the MP3 did to the recording industry. Meanwhile here is CP Grey, who makes fantastic youtube animated talks, describing why he thinks we're entering the Diamond Age, or the era of digital Aristotle.

If you're wondering what any of this has to do with philosophy, Edinburgh University has just launched its first philosophy MOOC.

Meanwhile, in the world of NSMOOCs (not-so-massive-offline-open-courses), the London Philosophy Club has two great events coming up, the first on November 27 has the clinical psychologist Peter Kinderman talking about the ethics of psychiatric diagnosis (including, I hope, the schizophrenia report); while on Tuesday December 4th, we're hosting Angie Hobbs, who is talking about the philosophy of flourishing.

Finally, can I encourage you to download this sermon by Mark Vernon, about the tricky place between Christianity and Greek philosophy in the modern world - and how philosophy sometimes leaves out the need for nurture and love which Christian communities sometimes provide.

PS Two kind people wrote reviews of my book on Amazon this week - it now has 25 reviews and is still rated five stars, which makes me very happy. Thanks also for your kind emails after last week's newsletter, with many of you saying you'd had similar moments of epiphany.

See you next week,

Jules