In the Hall of the Mountain King

Image by Matt Sclarandis from Unsplash

‘I’m finding it really hard. I’m worried that if I tell people the truth, they’ll put me in a strait-jacket. I’m afraid to tell my own husband.’

It’s June 2020, the middle of the COVID pandemic, and I’m in a room full of dead people. The official title of the gathering is the annual conference of the International Association of Near-Death Studies (IANDS), which brings together researchers into near-death experiences (NDEs) and ‘experiencers’ themselves, who have come back from what in some cases would technically be described as death, with vivid accounts of journeys beyond the veil.

This being the middle of a global lockdown, it’s a virtual conference, and I’m floating from zoom room to room like Dante in limbo, hearing the disembodied souls’ accounts of life on the other side.

In general, the reports are resolutely cheerful. The speakers have come back from death with shiny smiles that beam certainty. The more certain their accounts, the more successful their books, which have reassuring titles like Proof of Heaven, Heaven is Real, and I’ve Definitely Been to Heaven. Who would buy a book called Um…WTF was that?

For some perverse reason, I find myself more drawn to the ‘experiencers’ who are not totally at peace, nor totally certain what they encountered. Like Nancy Bush. She had an NDE in 1962, when in labour, during which her soul left her body and found itself in a dark place. Three giant circles hovered above her, switching colour from black to white. They told her that neither she, nor her child, nor anything else in her life was real. It was all a joke. She came back from this experience understandably crushed, and spent the next few decades researching distressing NDEs. They’re not always easy, and the re-entry to ordinary life can be bumpy.

My off-peak experience

20 years ago, I had what could be described as a near-death experience on the side of a mountain. It was in February 2001. Back then, I had suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder for six years, following a couple of LSD bad trips when I was a teenager. For six years, I became more and more lost and paranoid, a stranger to myself.

Then, in February 2001, my family travelled to Norway, to the Peer Gynt region, where my great-great grandfather had built a hytte. This is the hytte.

This year, for some stupid reason, we decided to go down the hardest slope on Valsfjel mountain. It was snowing, and visibility was poor. We set off down the run, which is particularly steep at the beginning and….

I smashed through a fence on the side of the slope and fell…

and fell…

I fell 30 feet and landed where the arrow points

The impact broke my left femur so the bone was sticking through the skin, as well as two vertebrae in my back. I also banged my skull and knocked myself unconscious.

Except I wasn’t unconscious. I was somewhere else, immersed in a white light, and completely filled with love. It felt like a luminous loving intelligence, that was both in me, and beyond me. It was the best moment of my life. I felt at home, as if I was suddenly reconnected to my soul or deepest self. For six years, I’d felt broken. Now, I had a powerful sense that there is something in me — in all of us — that cannot be broken, that cannot die.

I also realized that what had been causing my suffering all these years was my own anxious thoughts, which I could let go. I could relax and trust this treasure within me.

It reminded me, later, of those parables one reads about in mystical literature, in which a prince forgets his inheritance and goes begging in the street. That’s what I’d been doing — begging for the approval of others, when all the time within me (within all of us) was this white light, this pearl of great price.

The entire experience must have lasted about a minute, yet I encountered more wisdom in that minute than in whole decades of my life. Then I was back in my body. My uncle skied up and I heard him say ‘Oh God’. I tried to tell him that it was fine, wonderful in fact, that I’d had a peak experience (or should that be ‘off-peak’) but the words came out as gobbledy-gook. Then a motor-sledge came towing a stretcher, I was taken down to a cabin at the bottom of the mountain, and put on a table while they staunched the bleeding.

Shortly afterwards, my father came in to the cabin, my uncle having fetched him from our hytte. My father and I had not had a great relationship for the years immediately preceding the accident, because I was so uptight, anxious, and defensive towards the world. But it was a beautiful moment when he came into that shed — beautiful for me anyway, probably horrifying for him. All the antagonism between us evaporated, and I was simply his son, who had hurt himself.

A helicopter came and took me to Lillehammer hospital, and I went straight under the knife. I still have the metal pole in my leg that the surgeon put in that day. I spent a week in the hospital, then was flown back for another week in a hospital in London. I lost several pints of blood in the accident, and my muscles quickly atrophied, so I looked in a bad state. But I felt fantastic — not physically, but spiritually. I felt like the crash had re-connected me to myself, to my heart and soul. For five years, I had felt completely burnt out, like a heart in winter. Now it was like my heart thawed after a long winter. Through some miracle, I was handed a second chance at life. Can you imagine?

Searching for the white light

Alas, the euphoria died away. After two or three months, the old habits of anxiety and depression came back. I realized I needed a way to turn the insights handed me on the mountain into habits of thinking and feeling.

I heard about Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), which sounded like it was based on the same central idea that I’d encountered in my experience — that what causes our suffering is often our own beliefs. So I joined a CBT support group, practiced the exercises and did the homework, and it really helped me.

CBT, I later discovered, was inspired by the ancient Greek philosophy of Stoicism, and the insight of the Stoic philosopher Epictetus: ‘People are disturbed not by events, but by their opinion of events’. We make ourselves suffer when we look to externals for validation, like popularity, fame, power or money. Instead, Epictetus said we should trust what he called ‘the God within’.

For a decade, I followed the Stoic philosophy, and worked to revive it in modern life. I wrote a best-selling book about it that was published in 24 countries. Yet eventually I realized Stoicism is quite an individualistic, rationalist and lonely path. It helped me enormously, yet what initially helped me was not my own reason, but something beyond that.

What was that white light? Was it God? If so, which one? Was it my guardian-angel? Rewards for past karma? Some local mountain spirit? In fact, the mountain I injured myself on, Valsfjell, is famous in Norwegian mythology for being the home of the Mountain King in the myth of Peer Gynt. Peer knocks his head on a rock, is transported into the hall of the Mountain King, and learns the essence of the Troll Way: ‘Be true to yourself and to hell with the world.’ Not a bad summary of the message I’d received.

Studying NDEs

I didn’t speak about the experience for years, not even to loved ones, and looking back I wonder why. I think it was simply too weird. When people speak about NDEs, there’s a risk they come off as ridiculous, delusional, or attention-seeking. ‘Let me tell you about my NDE’ sounds a bit like ‘let me tell you about my past life as Cleopatra’. ‘I’m an experiencer’ sounds as self-regarding as ‘I’m an empath’ or, even worse, ‘I’m a light-worker’.

But gradually I started to research the topic, to see if I could get understand my experience better, and maybe get back to that white light.

There have been accounts of NDEs going back two millennia, all the way to the Upanishads, written around 700 BC, in which a boy dies and visits Yama, the Lord of Death. Yama tells him:

The Soul is not born, nor does he die,

He does not originate from anybody, nor does he become anybody,

Eternal, ancient one, he remains eternal,

he is not killed, even though the body is killed.

Plato’s Republic, the most famous book of western philosophy, also ends with an NDE account, the ‘Myth of Er’, in which Er ascends into heaven and sees souls continuously reincarnating according to their earthly deeds. Plato’s message is very similar to the Upanishads: this world is a dream, don’t get too attached to it, seek the white light of the Divine.

The earliest medical account of an NDE is from 1740, by a French military physician. He gives an account of one ‘LR’, who after a fever and blood-letting loses consciousness:

He reported that after having lost all external sensations, he saw such a pure and extreme light that he thought he was in the Kingdom of the Blessed. He remembered this sensation very well, and affirmed that never in all his life had he had a nicer moment.

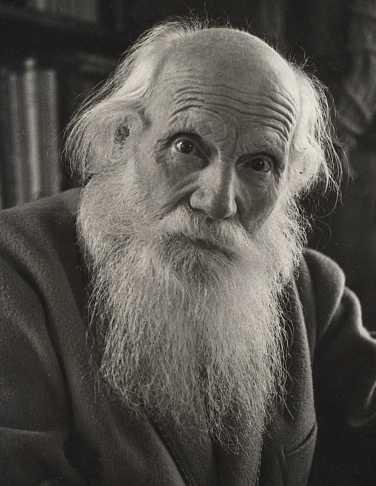

Albert Heim

The modern field of NDE research was launched in 1892, by the geologist and mountaineer Albert Heim, after he fell off the Santis mountain in Switzerland. He wrote:

I saw my whole past life take place in many images, as though on a stage at some distance from me. Everything was transfigured as though by a heavenly light and everything was beautiful without grief, without anxiety, and without pain…Elevated and harmonious thoughts dominated and united the individual images, and like magnificent music a divine calm swept through my soul.

Heim discovered that many other mountaineers had similar experiences when falling off mountains — a feeling of peace and detachment, a life-review, and a confidence that consciousness survives the death of the body.

Scientific research into NDEs took off in the 1960s, largely thanks to improved resuscitation procedures, which made it more likely that people survived cardiac arrests. Suddenly, thousands of people were returning to life after flat-lining. Many returned with remarkably similar accounts of spiritual journeys. These accounts were gathered together and published by the psychiatrist Raymond Moody, in his 1975 best-seller Life After Life.

People’s accounts of NDEs are so similar, that researcher Bruce Greyson even invented the ‘Greyson NDE scale’ to score the extent to which an NDE can be classified a ‘full NDE’. A top-scoring NDE ticks off all the typical features — an encounter with a ‘brilliant light’, feelings of peace, joy and unity with the universe, encounters with dead relatives, encounters with a guide or deity, a life-review, and then return to the body, sometimes with a particular mission. It’s an odd idea — that a scientific model can rate an NDE according to how ‘full’ it is (my experience only scores 5/10, so my memoir will be called Halfway to Heaven).

The similarities in people’s stories makes for a strong argument that NDEs are encounters with an actual spiritual dimension beyond the body. After all, why should so many people, including me, have experienced a ‘brilliant white light’? I had no knowledge of the NDE literature back then, and even if I had, it seems far-fetched that I could have conjured up this cultural artefact while in extreme physical trauma.

Yet not all accounts fit the Greyson model. And there are cultural differences — westerners are more likely to encounter Jesus, who sends them back to Earth with a spiritual mission, while Indians are more likely to encounter Yama, who sends them back after realizing they died through a clerical error. This idea of NDEs being caused by bureaucratic bungling in the underworld was quite common in ancient Rome, but never appears in modern western accounts.

NDEs aren’t always blissful encounters with a white light either. The 2014 AWARE study, the largest ever study of NDEs, interviewed over 2000 cardiac arrest survivors. About half recalled experiences after they lost ordinary consciousness. But only a quarter of their experiences fit the Greyson NDE model. Others involved fear and persecution, or strange encounters with plants and animals. The lead author of the study, Dr Sam Parnia, concluded: ‘the experience of death may be broader than previously thought and described as NDE’s’.

Another argument that NDEs are genuine spiritual journeys, rather than physiological tricks of the brain, is how vivid and coherent the experiences are. My body was completely smashed up, yet in 60 seconds I encountered life-changing wisdom. Other people had out-of-body experiences during operations, and came back with accurate descriptions of the operating theatres, even though their brains showed no EEG activity.

Whatever the cause, most people, including me, say such experiences are largely positive. We come back less afraid of death, and confident there is something on the other side that is benevolent and loving. But the re-entry to this life can be difficult.

A 2006 survey in the Journal of Near-Death Studies found that three quarters of ‘experiencers’ said it took them at least a decade to adjust to their experience. 80% said they felt ‘homesick’, and longed to return to ‘heaven’. 25% said the homesickness was so strong they’d considered suicide. 80% said they’d been felt misunderstood when they shared their experience with a loved one. Over half said they’d broken up with their partner as a consequence. Many said they weren’t sure what they were meant to do back on Earth.

I did my best to find that white light again. I became a Christian and surrendered to the Holy Spirit. I tried psychedelic therapy in Peru (where it’s legal). I tried meditation retreats, breathwork, sensory deprivation in flotation tanks. But I never found the light again, and don’t think I ever will in this life. I’ve come to accept that.

All of us will have moments in our lives we can’t fully explain, some wondrous, some horrendous. Perhaps we can learn to tolerate the ambiguity and mystery, without grasping for over-certain explanations.

Sometimes I forget that moment, and this world seems all there is. And sometimes this world seems made of gossamer thread, and that world feels far more real. I wonder if perhaps I have already completed the ‘task’ the light told me to do (it told me to write a book, which I did).

So now what?

Mountain King?

Hello?