7) Edward Bulwer-Lytton and the Coming Race

This is the seventh entry in my spiritual eugenics series, which explores the overlap between eugenics and New Age spirituality. You can find the whole series here.

You probably haven’t heard of Edward Bulwer-Lytton. If you have, it’s likely because he was the author of supposedly the worst ever opening sentence of a novel: ‘It was a dark and stormy night’ — a line so cringe, it’s inspired an annual prize for bad writing.

But in his lifetime, the Earl of Lytton was a Cabinet minister and one of the most successful Victorian novelists — his popularity rivalled that of his friend, Charles Dickens. When he was buried in Poet’s Corner of Westminster Abbey, Benjamin Jowett heralded him as ‘one of England’s greatest writers and one of the most distinguished men of our time’. His ‘catastrophic decline in popularity’ since his death is a lesson in how fashions change, and literary hype passes.

But there is one part of culture where Lytton had a huge and continuing impact: New Age spirituality. He was a key figure in the occult revival of the late-19th century. His ideas inspired the Theosophical Society and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, and through them contemporary New Age occulture.

We’ll look at three of his contributions to New Age culture and to our theme of spiritual eugenics. First, the idea of a secret order of superpowered magi; second, his idea of the ‘dweller on the threshold’; and finally, the idea of the evolution of occult superbeings. But we’ll begin with a little about his life.

The Victorian dandy

Edward was the youngest child of the pairing of two aristocratic and eccentric families, the Bulwers of Heydon Hall and the Lyttons of Knebworth House. He grew up in Knebworth, wandering around its estate, imagining himself as the hero of medieval romances and Gothic ghost stories.

Knebworth House

He married young, to an Irish beauty called Rosina Doyle Wheeler. It would prove to be one of the all-time worst marriages. Edward’s mother didn’t approve of the match, and cut off his inheritance. Forced to fend for himself, he became a novelist — an interesting career choice for a young aristocrat, but he was extremely diligent. Between 1827 and 1837 he wrote 11 novels, two long poems, one play, and a history of Athens in three volumes, as well as essays and reviews. He made an immediate smash with the scandalous tale of a high society dandy in Pelham (1828), and cemented his reputation with the historical drama, The Last Days of Pompeii (1834). He helped to develop numerous genres — the ‘silver fork’ high society novel, crime dramas, historical romances, occult fantasy and science fiction.

He was also an MP, initially for the Whig party, where he campaigned for parliamentary reform and the extension of the vote to the middle class. As an upcoming young radical, he was a friend and disciple of William Godwin, the Enlightenment philosopher and novelist. Bulwer-Lytton’s radicalism, however, was more abot aristocratic condescension than any genuine love for ‘the great unwashed’ (a phrase he coined). He was a very aristocratic libertine and dandy. His foppish clothes and elaborate facial hair earned him some ridicule. Leslie Mitchell writes:

It was hard to take the man seriously, and to add to the sense of the exotic Lytton would often receive visitors while smoking a pipe six or seven feet in length, or taking opium through a hookah. Interviews were offered in a room decorated in the style of Pompeii and lighted by ‘a perfumed pastille modelled from Mount Vesuvius

Zanoni and the idea of immortal superbeings

For our topic, Bulwer-Lytton’s most interesting book is his 1842 fantasy, Zanoni. In this book, for the first time, he explored his deepest interest — the occult.

He was a little reticent to share his occult interests too directly, so he created a distancing device — a tale within a tale. The story begins with the narrator in an occult bookstore in Covent Garden. He is searching for information about an ancient secret society called the Rosicrucians. He meets a mysterious old man in the store, who claims direct knowledge of the Rosicrucians. The next day, the old man hands over a manuscript with the tale of Zanoni — this is the rest of the novel.

Zanoni is a dazzling and mysterious young man who turns up in European high society, throws money around, and apparently has superhuman powers, including clairvoyance, mesmerism and the gift of eternal youth. It turns out he is one of two remaining initiates of a secret occult order — the Rosicrucians — although he may come from an even older order, possibly the Chaldeans of Biblical times. Zanoni falls in love with an opera singer, Viola. He hopes to train her up to become a superhuman magus like him.

Meanwhile, his master and mentor, Mejnour, appears. Mejnour is always looking for new adepts, despite the perils of initiation. Zanoni says to his master:

scarcely once in a thousand years is born the being who can pass through the horrible gates that lead into the worlds without! Is not thy path already strewed with thy victims? Do not their ghastly faces of agony and fear — the blood-stained suicide, the raving maniac — rise before thee, and warn what is yet left to thee of human sympathy from thy insane ambition?

But Mejnour has plans to create an occult master-race:

Can I forego this lofty and august hope, worthy alone of our high condition, — the hope to form a mighty and numerous race with a force and power sufficient to permit them to acknowledge to mankind their majestic conquests and dominion, to become the true lords of this planet, invaders, perchance, of others, masters of the inimical and malignant tribes by which at this moment we are surrounded: a race that may proceed, in their deathless destinies, from stage to stage of celestial glory, and rank at last amongst the nearest ministrants and agents gathered round the Throne of Thrones?

Mejnour recruits a young Englishman, Glyndon. But very quickly, the initiation process goes wrong. Glyndon proves too impure, and he fails a key test — the confrontation with the ‘dweller on the threshold’. All initiates must go through this confrontation, but Glyndon is unprepared, and he flees in terror. The dweller pursues him, destroying his life.

The finale of the novel is in revolutionary France. A ruined Glyndon is a friend of the French philosophes, who spout atheist materialism and ‘liberte, fraternite and egalite’. Zanoni the magus is not a fan of the revolution — materialism denies the higher truths of the soul, and equality is a lie. He believes in spiritual hierarchy:

The few in every age improve the many…Universal equality of intelligence, of mind, of genius, of virtue! — no teacher left to the world! no men wiser, better than others, — were it not an impossible condition, WHAT A HOPELESS PROSPECT FOR HUMANITY!

The revolution turns into a bloodbath, and the dweller on the threshold stalks the streets of Paris, reveling in the murder. Viola is imprisoned and sentenced to death, but Zanoni sacrifices his life for her. He exchanges the immortality gained by his occult knowledge for true Christian death and resurrection.

The elixir of life

The idea of the alchemical ‘elixir of life’ is very old, going all the way back to the Epic of Gilgamesh, and turning up in ancient Chinese and Buddhist literature, before re-appearing in medieval and Renaissance magic as the Philosopher’s Stone — a magic elixir which grants you eternal youth, possibly by turning you into gold (something Andrew Harvey discussed in our recent interview).

In the 17th century, the legend of the elixir was connected to a mythical secret society called the Rosicrucians, whose adepts supposedly possessed all knowledge and acquired superhuman powers like clairvoyance, telepathy, and radical life extension. The Rosicrucians were originally a fabrication, a literary myth, but the myth fascinated 17th-century intellectuals including Descartes, and may have inspired the ‘invisible college’ of the Royal Society — a group of early scientists who were likewise interested in how to extend human life.

In the 18th century, Enlightenment philosophers like the Marquis de Condorcet and William Godwin speculated that science would advance so far that misery, sin and death itself would be ‘hacked’ (to use contemporary parlance). Perhaps this would occur through natural science, perhaps through occult magic — at this stage, there was no firm boundary between the two.

Godwin, for example, despite being seen as the uber-rationalist of the late 18th century, was also fascinated by the occult, and wrote a novel, St Leon, about a Rosicrucian magus who attains eternal youth and ends up isolated and miserable. This inspired his future son-in-law, Percy Shelley, to write a similar novel, St Irvyne, or the Rosicrucian, also about a magus who attains immortality with tragic results.

Godwin’s daughter and Shelley’s wife, Mary Shelley, took up the theme in her 1818 novel, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus. Victor Frankenstein is a brilliant scientist-magus, who discovers the secrets of life, and constructs a superhuman. He flees from the Monster, who pursues him and ruins his life. The Monster begs his creator to make a mate for him, but Dr Frankenstein realizes this threatens the survival of humankind — if the two had children, they would create a master-race that would supplant and eliminate humanity.

Bulwer-Lytton was a friend of Godwin’s and the two often corresponded, and it’s likely Zanoni was influenced by these earlier ‘Rosicrucian novels’. He was also influenced by stories of the Comte de Saint-Germain, an occultist and adventurer who turned up in 18th-century Paris claiming to be 300 years old. He was almost certainly a charlatan but he’s become a legendary figure in New Age spirituality.

Lytton as occult adept

In addition to these literary influences, Bulwer-Lytton genuinely believed in the occult, and fancied himself a superhuman adept in the mould of Zanoni. His fantasizing and myth-making spilled over into his own life, as it often does with occultists.

He was fascinated by spirituality since childhood, and acquired an enormous library of occult books. He read up on all the latest spiritual-scientific fads — Mesmerism, water cures, phrenology — and carried out his own experiments to test telepathic connection (or ‘sympathy’) between snails. He learned fortune telling from gypsies and purchased his own crystal ball and magic wand. At Knebworth House, he held seances and told the fortunes of friends like Disraeli, presenting himself as ‘Le Vieux Sorcier’ and signing letters as ‘Merlin’. Among the occultists of high society, he was hailed as ‘the High Priest and Great Wizard of our Circle’.

His more rational friends were amused and dismayed by his taste for the occult. George Eliot tells a story, quoted in Mitchell’s biography of Lytton:

He is quite caught by the spirit of the marvellous, and a little while ago, at Dickens’s house, was telling of a French woman who could raise the dead, but only at great expense. ‘What,’ said Dickens, ‘is the cause of this expense in raising the dead?’ ‘The Perfumes!’, said Bulwer, with deep seriousness, stretching out his hand with his usual air of lofty emphasis.

Bulwer-Lytton was partly interested in the occult and the elixir of life because, as ‘perhaps the vainest man who ever lived’ (his words), he hated ageing and death. He reminds me of Dorian Gray (Oscar Wilde was a friend of his son) but alas for Lytton, in real life the man got older while his portraits got younger and younger. He seemed to believe that the artist-magus could achieve a personal immortality denied to the masses, through the intensity of his individual consciousness. He writes in his 1858 novel, What Will He Do With It?

the consciousness of individual being is the sign of immortality, not granted to the inferior creatures — so it is in this individual temperament one and indivisible, and in the intense conviction of it, more than in all the works it may throw off, that the author becomes immortal. Nay, his works may perish, like those of Orpheus or Pythagoras; but he himself, in his name, in the footprints of his being, remains, like Orpheus or Pythagoras, undestroyed, indestructible.

He believed in immortality only for the elite. Leslie Mitchell writes:

In his discussions of what the afterlife might be like, he was always clear that only people with certain spiritual qualities would achieve it. He did not expect to meet whole categories of people after death, among whom may be numbered savages, peasants and tradesmen. Few people could be artists. Few had ‘the nervous sympathy’ that was transcendental. After hearing his description of the spirit world, Harriet Martineau exclaimed, ‘How aristocratic you must be!’

[For more on this, read this]

The influence of Zanoni on New Age culture

Zanoni was a huge influence on the occult revival of the late 19th century. Its biggest influence was through Madame Helena Blavatsky, founder of the Theosophical Society. Her mother translated Lytton’s novels into Russian, and the young Blavatsky devoured them and absorbed their ideas into her new religious movement. She turned fiction into religious myth, claiming to be in contact with a secret superhuman order called ‘The Masters’, who sought to guide human evolution and create a new super-race.

The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn was also at least partly inspired by Lytton’s Zanoni and Aleister Crowley put the book on his recommended reading list for magical adepts. The idea of a secret order of superbeings influenced later fantasy fiction, from Algernon Blackwood and Dion Fortune (both members of the Golden Dawn), to Star Wars, Dune and Harry Potter.

Bulwer-Lytton’s invention of the ‘dweller on the threshold’ was also taken up by later occultists — Madame Blavatsky mentions it in her writings, as does Rudolf Steiner, who wrote a 1912 play called The Guardian of the Threshold. Joseph Campbell, in his Hero of a Thousand Faces, suggested that a key part of the hero’s journey is a confrontation with the ‘threshold guardian’. This may have inspired the moment in Empire Strikes Back, where Luke confronts the ghost of Darth Vader as part of his Jedi initiation.

The ‘dweller on the threshold’ also inspired David Lynch’s drama, Twin Peaks. FBI agent Dale Cooper is told of the legend of the White and Black Lodge (a Theosophical idea), and that every soul, on their journey to perfection, must confront the ‘dweller on the threshold’, a malevolent double. If they prove impure, the dweller will possess them.

It’s interesting to note that in Zanoni, the dweller isn’t a double, but rather a demonic woman, a succubus who claims the adept as her lover:

Its form was veiled as the face, but the outline was that of a female; yet it moved not as move even the ghosts that simulate the living. It seemed rather to crawl as some vast misshapen reptile… “Thou hast entered the immeasurable region. I am the Dweller of the Threshold. What wouldst thou with me? Silent? Dost thou fear me? Am I not thy beloved? Is it not for me that thou hast rendered up the delights of thy race?…Kiss me, my mortal lover.’

This, according to William Godwin, is the Rosicrucian secret of eternal life — you must take an elemental spirit as your lover. But I wonder if the Dweller on the Threshold didn’t have a more terrestrial inspiration — Lytton’s wife, Rosina.

Rosina Doyle-Wheeler

As mentioned, Edward and Rosina had a disastrous and violent marriage, with both apparently physically attacking the other. They eventually separated, but that was not the end of hostilities. Rosina felt aggrieved and unsupported, and she took to publicly harassing and ridiculing Lytton at every opportunity. She published a poem, ‘Nemesis’, detailing his flaws and offences. She would attend productions of his plays, and orchestrate booing and hissing. She wrote letters, sometimes 20 a day, addressed to ‘Sir Liar Coward Bulwer’ and distributed them to his clubs and Parliament. She accused him of every conceivable crime, including murdering their child and committing sodomy with Prime Minister Disraeli.

In 1858, when Lytton ran for re-election and was appointed Minister for the Colonies in Disraeli’s government, Rosina turned up on the campaign trail. When he saw her, he blanched and jumped over a garden fence to hide. Rosina climbed on the platform and recounted the litany of his crimes to the enthralled electorate. He subsequently had her sectioned for insanity, but she rallied supporters to her cause. The press had a field day. Lytton eventually got her released and paid her off, but she continued attacking him until his death. She was, in Dickens’ words, ‘the misfortune of his life’, his own personal nemesis.

The Coming Race

As he grew older, Lytton became increasingly embittered and reactionary. He was always, in fact, wary of mass democracy and a supporter of aristocratic elitism. He explored this theme in his final novel, the 1870 science fiction tale, The Coming Race.

In the novel, the American narrator falls down a cave and discovers a subterranean world, populated by a species known as the Vril-ya. They are a ‘race akin to man’s, but infinitely stronger of form and grandeur of aspect’. You can see their superiority in their physiognomy (a science in which Lytton believed): ‘the face! it was that which inspired my awe and my terror’.

Not only are the Vril-ya physically and mentally superior, but they have control of a magical force called the Vril — a cross between electricity and prana or ‘the force’. Vril enables them to communicate telepathically, to command automatons to do their bidding, and to destroy anything and anyone who stands in their way.

The capacity to control Vril is hereditary. The Vril-ya are an aristocratic republic — they recognize no ranks among themselves, but they look down on any tribes or races who can’t control Vril as inferior savages, who should be exterminated if they cause any trouble. It becomes clear to the American visitor that if the Vril-ya ever reached the surface of Earth, they would soon eliminate homo sapiens and take its place. They are ‘a race fatal to our own’.

The Coming Race was inspired by the publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species and the discovery of skulls of other hominids like Neanderthal man. Lytton wrote to his editor, John Forster:

The only important point is to keep in view the Darwinian proposition that a coming race is destined to supplant our races, that such a race would be very gradually formed, and be indeed a new species developing itself out of our old one…

It’s an ambiguous novel, which can be read multiple ways. Personally, I read it as a story about spiritual evolution and spiritual eugenics — the Vril-ya are an Aryan master-race who are destined to dominate all other races because of their superior spiritual abilities. That’s certainly how the book was read by later spiritual seekers like Madame Blavatsky. As we’ll see, she incorporated the idea of spiritual evolution into her religion of Theosophy, claiming that a new race of superhuman was now evolving, and it was the task of the Theosophical Society to prepare the way for this new type to take over the world. Her successor, Annie Besant, name-checked Lytton’s novel in her speeches, declaring: ‘We are living in an environment that is destructive of the higher evolution, and at our peril we leave it as it is when the Coming Race must inevitably be born’.

More directly, some enthusiastic readers even formed ‘Vril Societies’ — I’m not sure what these societies actually did, besides developing their telepathic power and perhaps drinking Bovril (a drink inspired by Lytton’s book). One such Vril Society apparently existed in the occulture of Nazi Germany, at least according to rocket scientist Willy Ley. In his article, Pseudoscience in Naziland, he describes the influence of various occult groups among Nazis, including one

literally founded from a novel. That group I am referring to called itself the Wahrheitsgesellschaft — Society for Truth — and was more or less located around Berlin, dedicating their time to the search for Vril

The members of the group, Ley says, ‘believed they had secret knowledge that would enable them to change their race and become the equals of the men hidden in the bowels of the Earth…The subterranean humanity was nonsense. Vril was not. Possibly it had enabled the British, who kept it as a State secret, to amass their colonial empire.’

This passage has inspired a lot of conspiracy theories about the Nazis living underground and using Vril to communicate with UFOs. It appears to be a fiction more than truth. What is true is that Adolf Hitler was inspired by a Wagnerian opera based on a novel by Lytton — Rienzi, about a Roman hero (you can read more about that here).

In the 1960s, The Coming Race enjoyed new popularity among psychedelic hippies, thanks to the 1960 best-seller Morning of the Magicians, by Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier. That book explored the idea of a secret order of superbeings living among us. It mentions Lytton’s ‘conviction that there are beings endowed with superhuman powers. These beings will supplant us and bring about a formidable mutation in the elect of the human race’. Robert Anton Wilson, the Californian occult conspiracist, also speculated that ‘the Rosy Cross order still existed and commanded the Vril force that could mutate humanity into superhumanity’ (Wilson may not have literally believed this but I’m sure some of his hippy readers did).

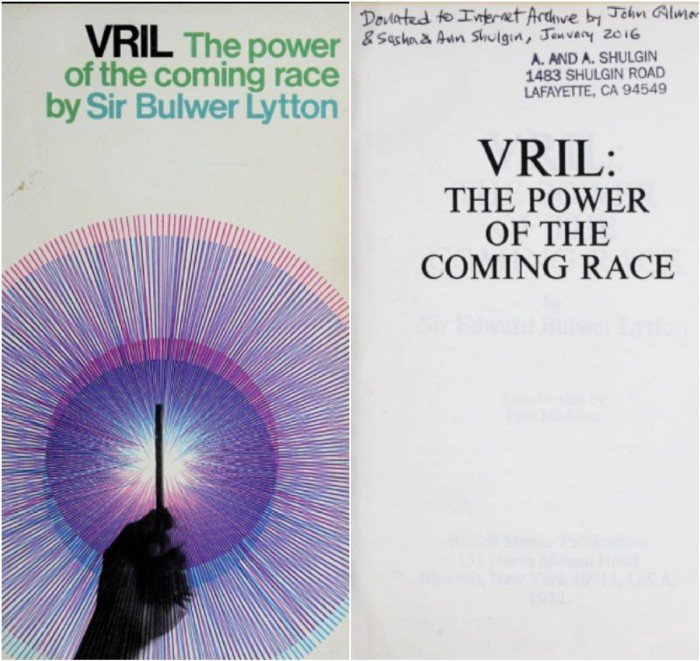

The idea of the Vril and a spiritual super-race appealed to psychedelic hippies, as it did to the Nazis, because they were all too ready to think of themselves as this new super-breed. Interestingly, by the by, I came across this 1960s edition of The Coming Race, and discovered it was owned and signed by Alexander Shulgin, pioneering psychedelic researcher and discoverer of MDMA. I’ll get into the eugenicky aspects of psychedelic culture later in this project.

Keeping up with the Lyttons

Lytton was not quite the superhuman adept he liked to suggest he was. This was a man who jumped over a garden fence to avoid confrontation with his wife. Nonetheless, he was a very successful novelist, and although his popularity has faded, his influence lives on in the New Age.

His descendants, meanwhile, helped to spread Malthusian and eugenic policies into the mainstream, and impose them onto millions of people. His son Robert Bulwer-Lytton was appointed governor of India — an unusual choice, when even his own government admitted he was mentally unstable. He was tasked with organizing the durbar to celebrate the crowning of Queen Victoria as empress of India. For this, he organized the largest meal in history, in which some 68,000 functionaries were fed.

While they feasted, millions of other Indians starved in the Great Famine of 1876–1878, a crop failure made much worse by Robert Lytton’s social Darwinian and Malthusian policies. He was, in his own words, ‘profoundly persuaded that every rupee superfluously spent on famine relief only aggravates the evil effects of famine, and that in all such cases waste of money involves waste of life.’

The British did provide some relief to the starving Indians, shepherding them into Malthusian ‘relief camps’ where they had to work for their food allowance. This allowance was fewer calories than prisoners would be given in Nazi camps, and the mortality rate in these relief camps was estimated at around 90%. Scholars estimate between five million and 10 million Indians died in the famine. Robert Bulwer-Lytton has been nicknamed ‘India’s Nero’ for his role in the ‘Indian holocaust’.

Two of Robert’s children — Victor and Emily Bulwer-Lytton — were founding members of the Eugenics Education Society, set up in 1909. The Eugenics Society helped to spread the creed of eugenics around the world — as we’ll see, it was most enthusiastically adopted by Nazi Germany. Emily, a vegetarian feminist occultist, would eventually leave the Eugenics Society and join the Theosophical Society instead. As we’ll see in the next chapter, they had their own brand of spiritual eugenics.

Sources:

Lawrence Poston, ‘Beyond the Occult: The Godwinian Nexus of Bulwer’s Zanoni’

Marie Roberts, ‘The Development of the Rosicrucian Novel, from Godwin to Bulwer-Lytton’

David Seed, Introduction to The Coming Race

JH Montgomery, Bulwer-Lytton’s Mystic Novels: On the Margins of the Invisible

Leslie Mitchell, Bulwer-Lytton: The Rise and Fall of a Victorian Gentleman

D.E Latane, ‘Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s Committal of his Wife to a Private Mental Hospital’

Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier, Morning of the Magicians

Robert Anton Wilson, Masks of the Illuminati