The Hari Krishna movement, and the West’s awkward romance with ‘global Hinduism’

Penguin India’s promotion for Sengupta’s new book

The 20th century was an extraordinary moment in Hinduism’s encounter with the West. For centuries, Hinduism had not expanded beyond India’s borders. Instead, India was colonized by Muslim rulers in the 16th century and invaded by Christian missionaries in the 19th century. But this one-way traffic changed on September 11 1893, when a 30-year-old swami called Vivekananda stepped on to the stage at the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago, and stole the show, presenting India as a land of unique tolerance and spirituality.

After him, a steady stream of Indian gurus found fame and followers in the US, especially in the 1960s and 70s. Maharishi Mahesh, Bikram Chowdury, Bhagwan Rajneesh, and more recently Sadhguru have all sold their modernized forms of Hinduism to a hungry western audience. Perhaps the least likely of these visiting gurus, though arguably the most successful, was Srila Prabhupada, the founder of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), commonly known as ‘the Hari Krishnas’. A new biography of Prabhupada by Hindol Sengupta, Sing, Dance and Pray, celebrates his life, and suggests he was the most important figure in ‘global Hinduism’, after Vivekananda.

What’s so unusual about Srila Prabhupada is that he started his mission so late — he came to the US and founded ISKCON in his 70s. And despite being a deeply conservative man, he managed to strike a chord with western hippies, attracting followers including Allen Ginsberg and George Harrison. But the love affair between Hinduism and hippies was destined to be stormy.

Abhay Charan, as he was originally known, was born in Calcutta in 1896, into a well-off family, who arranged his marriage when he was 22 to an 11-year-old girl. It wasn’t a happy marriage. He ran a successful pharmaceutical company but was much more drawn to the spiritual life, and he took renunciatory vows when he was 37 and left his family to be a monk when he was 54. His guru encouraged him to take their brand of Vaishnava Hinduism to the US. So in 1966, this elderly un-photogenic monk arrived in New York, with barely any money or even a place to stay.

He found a room in in the crime-ridden, rat-infested Bowery, and gradually attracted an audience for his teachings. He taught the need to open your mind to ‘Krishna consciousness’, a state of love embodied by the god Krishna. He also taught that you could find Krishna by singing his name, as the Vaishnava prophet Lord Chaitanya had taught in the 15th century.

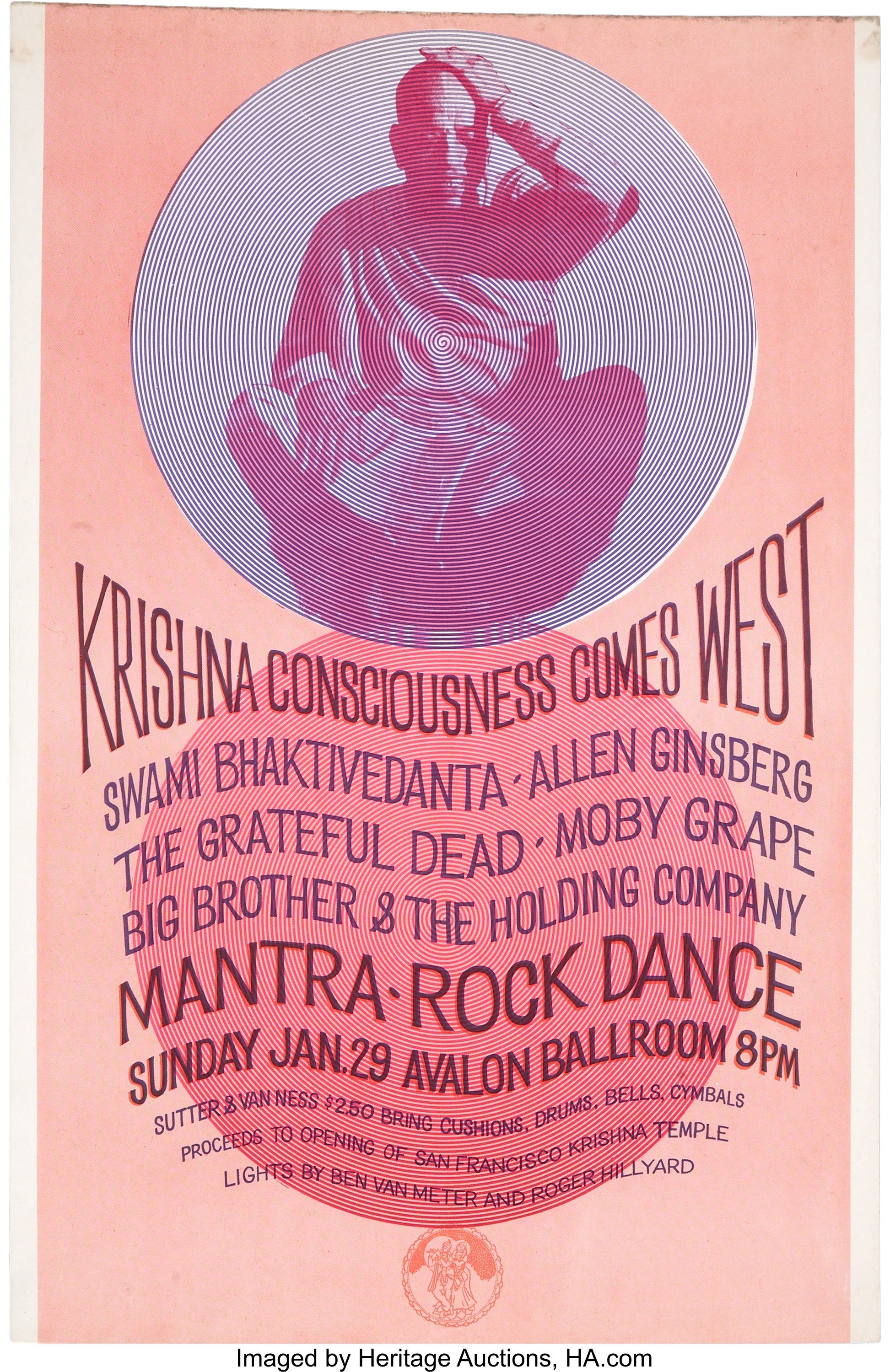

Singing and dancing in the name of love was a good pitch to the beatniks and hippies of the Bowery, and the Swami started to find followers. Some of them shaved their heads, put on saffron robes and took vows — no sex outside of marriage, no intoxicants, no meat, no possessions and lots of chanting. They started to sing and dance in public, one more freaky scene in Sixties America. Perhaps critically, they also offered cheap, good vegetarian food — Sengupta even shares their menus. Check out this groovy Krishna rave in San Francisco, the year after Prabhupada arrived.

An important early disciple was beat poet Allen Ginsberg, who chanted Hari Krishna on the William Buckley show’. After a long rendition, Buckley quips ‘that was the most un-hurried Krishna I ever heard’. Ginsberg arranged for Prabhupada to headline the ‘Mantra Rock Dance Party’, next to the Grateful Dead, in 1967. You have to applaud Prabhupada for his flexibility in the service of Krishna. He thought the US was a demon-ridden basket-case heading for apocalypse. Yet there he is at the Avalon Ballroom, spreading Krishna-consciousness to the drugged-up audience. He seemed to have genuine affection for his hippy followers, and praised their western versions of the Krishna chant.

Ginsberg asked Prabhupada’s opinion on LSD. He mentioned that his friend and fellow Hindu convert, Ram Dass, had been told by his guru (Neem Karoli Baba) that Krishna had reincarnated in the form of LSD because westerners would only believe in something material. Prabhupada disagreed. Drugs were bad. With Krishna-consciousness, you could stay high forever. Ginsberg’s psychiatrist arranged to send the many acid casualties he encountered to ISKCON, to help them integrate their experiences.

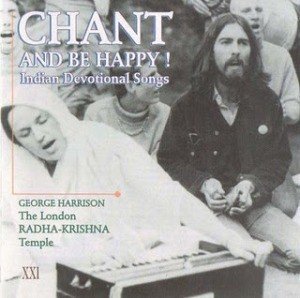

Prabuhpada launched a publishing arm that produced and distributed nearly a million books a year, which funded ISKCON’s programme to build hundreds of enormous temples to Krishna around the world. He also made a record of himself and others chanting the Hari Krishna chant, which became popular with tripping hippies.

George Harrison and John Lennon heard that record. In 1967, they had returned from an abortive trip to India to meet Maharishi Mahesh and learn Transcendental Meditation. They were taking a lot of drugs and the band was beginning to fall apart. George and John found solace in the Hari Krishna chant, once singing it for hours while driving from France to Portugal. An ISKCON disciple sought George out, they met, and George agreed to support the organization. He let Prabupada and his disciples stay in his country mansion (indeed, he donated the mansion to ISKCON in 1973) and Harrison recorded the Hari Krishna Mantra at Abbey Road in 1969 — it was featured on Top of the Pops and went to number 12 in the charts. Harrison later released an album of Hari Krishna music, and his biggest solo hit, ‘My Sweet Lord’, is a hymn to Krishna.

The marriage of ISKCON and hippy culture always had some tensions and paradoxes in it. Prabhupada left Harrison’s country-house in 1968 when John and Yoko took to wandering around naked. For his part, Harrison didn’t much like the hordes of Hari Krishna evangelists at western airports using his name to sell their books and attract disciples. Sengupta hints at deeper problems in his biography. Prabhupada was an old man when started ISKCON, he suffered a heart attack on his way to the US, and he was often weary and annoyed by the poor discipline of his followers. Many of them were hippy wastrels from the streets, attracted by the chanting and free food, but hardly capable of the strict life of a sannyasin. Sengupta mentions that Prabhupada had some problems with rebellious disciples, but that’s about as far as criticism goes.

In general, I don’t think it’s unfair to describe this book as a hagiography — a medieval-style celebration of the life of a saint. It’s an official biography backed by ISKCON and published by Penguin India, who have previously published several ISKCON books (they have another ISKCON best-seller at the moment with ‘Icons of Grace’). The book’s publication was celebrated by leading Hindu nationalists, including the president of India. The main message of the book could be summed up as ‘look at how this Hindu saint took the West by storm’. But a medieval-style hagiography is less interesting than an honest biography. What’s missing?

President of India Ram Nath Kovind (centre) with members of ISKCON and copies of Sing, Dance and Pray.

ISKCON’s flower-power exterior can disguise quite how traditional Prabhupada was in his beliefs. You can hear recordings of his conversation online, and hear his opinions for yourself. He believed western civilization was ‘soulless’, bestial, demonic and heading for collapse, at which point there would be a ‘Krishna revolution’. Society ‘should revert to the Vedic principles, that is the four varnas’ — in other words, brahmans at the top, then kshatriyas (warriors), then the vaishyas (farmers), then the sudras (workers), and below them, the outcastes and mlecchas, ie the demon-infested non-Vedic people. The reintroduction of the varnas was, said Prabhupada, ‘50% of my mission’.

What would a varna-based society mean in a western context? Western people ‘are Aryans and ksatriyas in their origin’, but ‘due to bad association with the aborigines [sic], they have taken all bad habits and become degenerated. Now we have to revive this Aryan civilization and rectify things’. Black people are ‘sudras’ and ‘sudras don’t have a brain’; they are ‘uncivilized’ and ‘criminals’; ‘Sudra’ is to be controlled only. They are never to be given freedom…The blacks were slaves. They were under control. And since you have given them equal rights they are…always creating a fearful situation’. Education should be confined to ‘only the brahmanas’ [ie the highest caste]. The sexes should be separated and not mingle indiscriminately. Children should be sent to Vedic boarding schools aged five. Girls ‘should be taught how to sweep, how to stitch…clean, cook, be faithful to the husband’ — they are inferior beings, due to their karma. Prabhupada occasionally suggested polygamy should be allowed for men from the highest varnas. Homosexuality was ‘demoniac’ and evidence of the West’s bestial culture. Ultimately, the ‘hell’ of liberal, industrial, scientific civilization would fall, and an ‘ideal society’ of Vedic farms would arise.

There was clearly a difference between the face he presented to hippy America, and his actual, deeply-conservative beliefs. He wasn’t an extremist, merely the sort of illiberal, anti-modernist one would expect a pious 70-year-old Hindu monk to be. One of his western disciples, Bhakti Vikasa Swami, writes: ‘At the outset…he spoke little about his social plans. As an expert teacher, he did not attempt to do the impossible among the wild and uncouth hippies who mostly comprised his early followers….it was not until several years after incorporating ISKCON that he began to press his disciples to institute varnasrama-dharma [in other words, a caste-based, gender-divided theocracy].

Sengupta only mentions Prabhupada’s social views in one paragraph. He writes that Prabhupada ‘embraced questions about race and gender, constantly trying to explain that divisions as they existed, including racism and patriarchy, were in the realm of the material world — before the beatific gaze of Krishna, everyone was the same’. Yes, in a way everyone that exists is Krishna, but here on the earthly plane Prabhupada taught traditional Hindu hierarchies of power.

Nor does Sengupta describe what happened at the schools that Prabhupada introduced. He taught that boys and girls should be sent to single-sex Vedic boarding schools aged five. Many children of ISKCON disciples were sent to these schools in the 1970s and 80s, and truly, they were sent to hell. American boys were sent, aged five, to ‘schools’ in India without electricity, water or even glass in the windows, where dysentery was rife and the young boys were starved, beaten and repeatedly raped by the teachers and older boys. While they went hungry, ISKCON channeled its funds into the construction of huge temples nearby. The girls were sent to schools in the US where they were taught they were inferior beings, and given only the most basic education (they were taught the moon landings were faked, for example). They were also often mistreated, abused and sometimes raped. Parents and children were encouraged to remain ‘detached’ from each other, and barely saw each other — the parents were too busy providing free labour for ISKCON. In 2000, 95 former students sued ISKCON for $400 million, claiming that around 1000 children were abused at ISKCON schools over 20 years, and that Prabhupada knew about it and didn’t report it to the police. In 2005 they received a $9.5 million payout, after ISKCON declared bankruptcy. Sengupta doesn’t mention a word about this, instead devotes pages of his book to effusive eulogies from western disciples.

For a good if harrowing account of the abuse at the ISKCON schools, watch this documentary:

Nor does Sengupta mention a word about the controversy over Prabhupada’s succession. When he died in 1977, he was succeeded by 11 disciples, who each ruled their own fiefdom. E. Burke Rochford, Professor of Sociology and Religion at Middlebury College and an expert on ISKCON, told a documentary: ‘There is a real question whether they were appointed or appointed themselves. What we do know is of those 11, the majority of them have fallen down in one way or another.’ Indeed, one of the successors who ran a centre in Virginia was convicted of racketeering, mail fraud and ordering the contract killings of two wayward disciples. There are followers of Prabhupada who question whether he died of natural causes — in his last weeks, he claimed he was poisoned (you can listen to him say that here).

Sengupta doesn’t discuss Prabhupada’s legacy at all, other than to say he failed to establish a movement in India, but gloriously succeeded in the West. Today, ISKCON does survive in the West, but the vast majority of its followers are Indian expats. Why, if ISKCON was such a phenomenal example of ‘Global Hinduism’, is this book only published in India, and not in the West? Why did Penguin India publish a one-sided hagiography, while recalling more scholarly works like Wendy Doniger’s The Hindus in response to Hindu nationalist protests? Why? Perhaps because that is the reality of business in Modi’s India. That’s the way to make money, win powerful friends, and avoid ugly scenes.

Prabhupada came to the US in a more optimistic moment, when cultural globalization was taking off and India and the West were in something of a love affair. We’re in a more anti-globalist moment now, when it can feel everyone should ‘stay in their lane’ and stick to their own cultures. I hope that doesn’t happen. ‘Global India’ has enriched the West, through its culture, its food, its spirituality and its people. 30% of Americans have tried yoga. Four ministers in the UK cabinet were born in India. When the UK voted for its favourite dish, it chose Chicken Tikka Masala.

But let’s be honest about some of the challenges in Hinduism’s interaction with the West. ‘All religions are true’, Vivekananda declared. But all religions have their dark sides. All religions bring out the best and the worst in our natures. Hinduism at its best always had a capacity not just for ecstatic devotion, but also for critical self-assessment — there are countless examples, but I think of Ram Mohan Roy, who is buried in my hometown of Bristol, and how he criticized Hindu superstition in the 18th century. A self-confident and global Hinduism doesn’t need to hide its flaws.