A kestrel for a knave

I was recently out for dinner with two friends, who had both been to see a famous shaman in Glastonbury, by the name of Kestrel (pictured right). ‘Our futures are quite intertwined’, one of them remarked. ‘Similar things are destined for us.’ As they compared notes, we realized quite how similar their destinies were: Kestrel told them both they were going to write nine books.

This rang a bell. Another friend of mine had visited a shaman two years earlier. He’d also emerged with the exciting news that he was destined to write nine books over the course of his life. I texted him and asked him the name of the shaman. Sure enough, it was the same shaman, Kestrel. ‘Well’, said my friend. ‘It might still be true.’ I decided I needed to visit Kestrel, to discover what the future could possibly hold for me.

These days, everyone is a shaman. The term first came to public consciousness in the 1960s, through the English translation of a book by religious scholar Mircea Eliade, called Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Eliade argued that there was a primal stage of religion, in all cultures, before religions became institutionalized. Medicine men or women, called shaman in Mongolia or curanderos in the Americas, communicated with the spirits using ecstatic techniques like singing, drumming, and psychoactive substances. They could use their spirit-allies for healing or for sorcery.

The shaman became a magical figure in the New Age counterculture. The West discovered magic mushrooms thanks to a Mexican shaman called Maria Sabina, who kindly included an American tourist in a mushroom ceremony. The tourist wrote about his trip in Life magazine, in 1955, causing a horde of hippies to descend on her village and run rampage. Eventually, the Mexican army was called in to kick them out. Maria Sabina complained the mushroom spirits no longer sang to her.

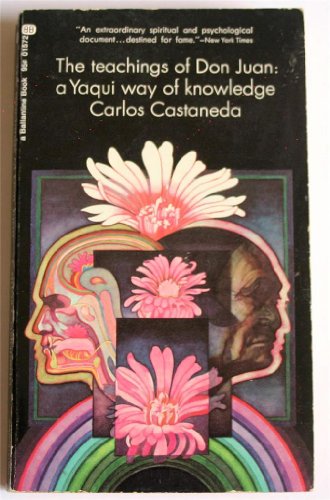

In 1968, popular interest in shamanism surged with the publication of The Teachings of Don Juan, by a Stanford anthropology PhD called Carlos Castaneda. Carlos claimed to have been initiated by a Mexican wizard called Don Juan. Later, it turned out Don Juan was made up, but that didn’t really matter. What is truth anyway?

Castaneda’s fake apprenticeship raised the intriguing prospect that westerners could become shamans themselves. The first to try was the Surrealist Antonin Artaud, who took part in a peyote ceremony in Mexico in the 1930s. He thought peyote offered him ‘a way of no longer being ‘white’, that is, one whom the spirits have abandoned’.

Alas, he went mad, but others were more successful. In the 1970s, an American anthropologist called Michael Harner went native while studying the Jivaro in the Amazon. Following powerful spirit-encounters on ayahuasca, he trained to become a shaman, then set up a training programme for western shamans.

Shamanism has gone mainstream in the last decade thanks to the boom in psychedelic tourism. Tens of thousands of westerners now travel to the Amazon to benefit from local shamans’ botanical knowledge and psychedelic expertise. I went to the Amazon myself two years ago, for a nine-day ayahuasca retreat, and am still making sense of my experience. It’s a bungee jump into a completely different universe, populated by plant-spirits and morally-ambivalent sorcerers.

Once you’ve tried ayahuasca, it’s easy to decide you are a shaman too. Hence the rise of the western shaman, complete with drum, spirit-allies, feathers in their hair, and names like Starhawk or Kestrel.

This appropriation offends some indigenous shamans, but it’s difficult to copyright a religion that is so de-centralized. And shamanism has a lot of appeal for Westerners. It’s very old, non-hierarchical, nature-worshipping, open to the ‘sacred feminine’, and it exists mainly as an oral culture, which means it’s whatever you want it to be. It’s a good religion for a time of institutional collapse.

Shamanism is now a growing niche in the trillion-dollar wellness industry. This year, a shamanic clinic called Guardian Angel opened in Mayfair, offering one-on-one sessions for £295. Luxury hotels like the Faena hotel in Miami now have in-house shamans. In Silicon Valley last summer, I met a corporate shaman who consults the spirits for her clients. Viewers of ITV This Morning got to see host Eamon Holmes exorcised on live TV by celebrity shaman Durek, who is also the boyfriend of Princess Martha of Norway.

As for Peru and Colombia, you can’t move for the fake-shamans offering their services to tourists. Some rob or rape their clients, leading to calls for a shamanic code of conduct, or a website where people can rate shamans, like Tripadvisor.

‘A lot of people have jumped on the bandwagon’ admits Kestrel. I’m at his healing clinic in Glastonbury. He’s been here 30 years and has seen the shamanic bubble grow. But few competitors can boast the client list he reels off to me: Russell Brand, Sally Hawkins, Nicholas Cage (he’s also a shaman, by the way). .

We sit in the consulting room. I’ve gone for the cheap option - £40 for a half-hour. I tell him I’m at a crossroads. I’m wondering whether to continue my path as a writer. I’ve written two books but…should I continue?

He doesn’t need much prompting. ‘The first thing I’m getting from the spirit world is that you should continue with the writing. You’re going to write nine books.’

I don’t have the gall to confront him with the fact he gave the same prediction to three friends of mine, but I mumble that he’d also told one friend of mine they’d write nine books. ‘Do I tell everyone that?’ he says hurriedly. ‘No. It’s a sacred number. The number of completion. Any more questions?’

It’s potentially harmful to give people such certain predictions. Kestrel told both me and my friend we’d meet our soul-mates at the end of the year. He told my friend she should try and stay celibate until then. That was last Christmas.

But isn’t the fault as much ours, for throwing money at people to tell us our future? It seems even in the new, decentralized, non-hierarchical spirituality, we still yearn to be told what to do.

Anyway, Kestrel told one of my friends his nine books ‘wouldn’t necessarily all be written in this lifetime’. Maybe everyone will write nine books eventually.